Is your manager a tyrant, a coach, or a ghost? Whether we realize it or not, we have all experienced or exercised a management style inherited from a specific era. Yet, these postures are often oversimplified as mere personality traits. This is a mistake.

From the factories of 1900 to modern agile startups, every style has its own logic and history. Understanding these origins means moving beyond simply “enduring” management to actively choosing the one that fits your team today. Let’s return to the roots to unlock your potential.

The Classical School: The obsession with Efficiency#

Management found its foundations at the end of the 19th century, in a context of massive industrialization where the priorities were predictability and large-scale efficiency. The “classical” approaches, led by Frederick Taylor, Henri Fayol, and Max Weber, answered a clear need:

- Organize work,

- Reduce variability,

- Maximize production.

In this model, the manager is primarily a system conductor, the guardian of processes, rules, and execution. Power is centralized, communication is strictly top-down, and compliance is the main lever for performance. This model, fundamental for structuring organizations, corresponds to what we now call command-and-control management.

However, by the early 20th century, limits began to appear, limits that product and agile organizations still know very well:

- Rigidity in the face of change,

- Low employee engagement,

- Difficulty fostering innovation.

The 1930s Shift: When the human element entered the equation#

In the 1930s, Elton Mayo and the Human Relations movement demonstrated that motivation, a sense of belonging, and recognition have a direct impact on performance. This realization is now central to modern teams, where engagement and purpose are key drivers.

Meanwhile, Kurt Lewin’s work on group dynamics laid the groundwork for what would later be called adaptive leadership. By identifying different forms of leadership and their effects on behavior, Lewin paved the way for a situational reading of management: the leader’s role is no longer just to decide, but to create the conditions for collective performance.

Kurt Lewin identified three main leadership styles:

- Authoritarian (or Autocratic): Characterized by centralized control. The leader makes all decisions and sets the rules. This can increase short-term productivity but stifles motivation, creativity, and engagement.

- Democratic (or Participative): Involves group members in decisions. It fosters dialogue and cooperation, strengthening motivation and innovation while maintaining stable productivity.

- Laissez-faire (or Permissive): Minimal leader intervention. It allows total autonomy. This works with highly experienced experts but risks disorganization and conflict if the group lacks structure.

Long before these ideas became standard, Mary Parker Follett proposed a radically modern vision. She advocated for co-construction—power exercised with others rather than over them.

I am convinced her writings should be read by every manager. Her modernity is striking: although she lived during the classical era, she anticipated the conclusions of the Human Relations school and servant leadership by decades.

This transition marked a decisive turning point: the manager gradually stopped being a mere hierarchical relay and became a facilitator, a leader at the service of the team. Agile practices are not a break from history; they are its logical conclusion.

The Era of Motivation: Psychology meets the factory floor#

In the 1950s and 60s, management began systematically integrating the human factor. Rensis Likert refined Lewin’s work by focusing on the relationship between the manager and subordinates. He identified four systems:

- Exploitative Authoritative (hard, centralized authority),

- Benevolent Authoritative (paternalistic),

- Consultative (partial involvement),

- Participative (advanced democratic governance).

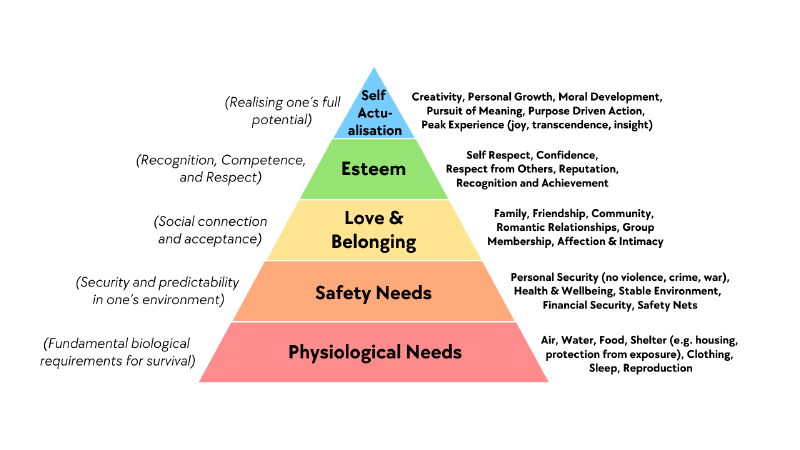

At the same time, Abraham Maslow proposed his famous hierarchy, ranking human motivations (physiological, safety, belonging, esteem, self-actualization). His contribution highlighted that sustainable performance depends as much on satisfying these needs as it does on work organization.

These approaches paved the way for more participative and motivating practices that would permanently influence modern management.

Production vs. People: Finding the perfect balance#

Building on Lewin and Likert, Blake and Mouton (1964) proposed an approach centered not just on power, but on managerial priorities. Their grid rests on two axes:

- Concern for Production,

- Concern for People.

By combining these dimensions, they identified five archetypal styles, ranging from the Impoverished (1,1) style (low concern for both) to the Team Management (9,9) style—the “Holy Grail” where performance and engagement are simultaneously prioritized.

In agile and product-oriented organizations, this evolution is particularly visible. The manager (or Tech Lead) acts as a system facilitator. Where classical models asked “who decides?”, contemporary practices focus on “how do decisions emerge?”.

Emotional Intelligence: The key to modern leadership#

In the late 1990s, Daniel Goleman marked a new milestone. Drawing on emotional intelligence, he stopped looking for an “optimal” style and instead analyzed how leadership influences the team climate based on context.

Goleman identified six styles (Coercive, Visionary, Affiliative, Democratic, Pacesetting, Coaching). His major contribution? It’s not about adopting one dominant style, but knowing how to consciously switch between styles depending on the team’s maturity. This resonates directly with agility, where leadership is inherently adaptive and distributed.

A Pragmatic Approach: Matching Style to Autonomy#

Theories are fascinating, but how do you apply them at 9:00 AM on a Tuesday? For a framework to be useful, it must be actionable. That is why my reading of situational management focuses on one simple data point: the level of autonomy of a collaborator regarding a specific task.

- Low Autonomy (Directive Style): Necessary for a junior or a new task. The manager clarifies the what and the how to secure execution.

- Developing Autonomy (Participative Style): The manager discusses options and listens but still makes the final call. This is the key phase for skill development.

- Intermediate Autonomy (Collaborative Style): The decision is made by the collaborator. The manager supports and validates the framework but no longer decides.

- High Autonomy (Delegating Style): The manager focuses on the result and the deadline without interfering in the how.

This axis is continuous. The same collaborator might require directive management on a new technology while being completely autonomous in their core expertise.

Conclusion#

The history of management teaches us that there is no style that is inherently superior to others. The myth of the “kind” manager who never gives orders is just as dangerous as that of the omnipresent “micro-manager.”

Effective management is not the one that matches your personal preferences, but the one that accurately adapts to your team’s situation. So, which style do you use most often by reflex? Perhaps it is time to try the one that feels the least natural to you.

- The Situational Leadership® Model

- Management 3.0

- Prophet of management by Mary Parker Follett (livre)

- Primal Leadership: Unleashing the Power of Emotional Intelligence by Daniel Goleman (livre)